In the Beginning Was The Cultivation of Sugar

Sugarcane (Saccharum) is perennial grass (Poaceae family), and native to the warm, temperate tropical regions of India, Southeast Asia, and New Guinea. It was first domesticated in New Guinea, and later in China and India in prehistoric times. From there it spread to the Middle East and Mediterranean about 500 AD. Later, in ancient Greece it was introduced for medicinal purposes, and people started using it as a desired sweetening spice, being known as sweeter than honey.

Sugar became indeed so popular and expensive that Arabian traders started their own sugar cane plantations in Arabia beside trading sugar cane from India in medieval times.

Sugar was one of the most demanded commodities throughout Europe, and it was referred to as the “white gold”.

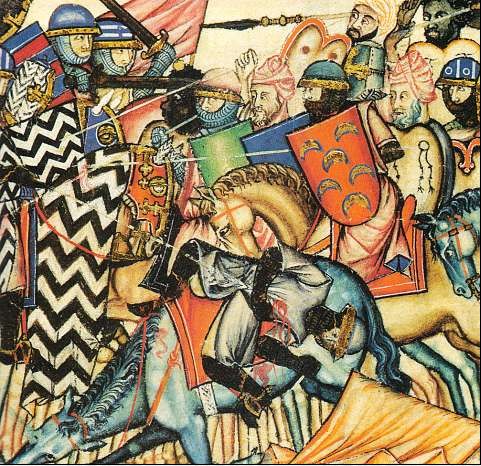

Reconquista is the Spanish/Portuguese term for the emergence and expansion of the dominion of the Christian empires of the Iberian Peninsula that were under the suppression of the Arabs. The Battle of Covadonga in 722 is considered the starting point, whereas the capture of Granada by the Catholic Monarchs on January 2, 1492 marks the end of the Reconquista period.

Arabs in Europe

The so called early Islamic conquests (also called Muslim/ Arab conquests) were territorial, religious and cultural expansions of the Arabs from the mid 630s into the 8th century into Europe and the former Roman territories. With the beginning of Islamic expansion the end of antiquity was marked, and Arabic traders were gaining large access to new European markets, a modern era of trade began, including the trade for the very desired commodity of sugar.

With the ending of the Reconquista period, the Portuguese began to further break the Arabian power by conquering territories along the African coast, likely seeking to break the very profitable Arabic trade monopoly for eastern sugar and spices. While there are several attempts of historians to explain why Portugal became the seaborne empire before other European nations in the 15th-16th century, it is without question that it was Portugal that prepared the way for industrializing sugar in the New World.

Portuguese Feitorias

In 1445 the Portuguese build the first feitoria (Portuguese for factory/ trading post) on Arguin (today Mauritania) on the West African coast. Portuguese feitorias were fortified trading posts in coastal areas with the goal to dominate and control the local trade for the Portuguese kingdom. Around the same time the Portuguese started to engage as first European nation in the African slave trade, and the slave economy should become one of the main sources of income of the Portuguese crown and the Portuguese economy. In the next decades Portugese feitorias were established along the African Coast south to Guinea, along the African coastal islands including Cap Verde, Sao Tome and Principe who became important sugar producing islands, whereas the Canary Islands should develop into the most important business hub for transports towards the Americas.

Madeira Island

In the 1420s a Portuguese expedition rediscovered the island of Madeira, and started its colonization shortly thereafter. The climate of the island was ideal for farming, and made the island a profitable outpost. From the 1460s onwards, grain cultivation ceased gradually on Madeira and was replaced by the more profitable newly established sugar cultivation. As sugar plantations are labor intensive, the Portuguese started to import the first slaves from the African coast. The systematic integration of slave labor from early on made the newly established sugar industry even more profitable. The city of Funchal exported sugar in 1472 not only to the Portuguese mainland thus established a close economic trade between Madeira and Flanders.

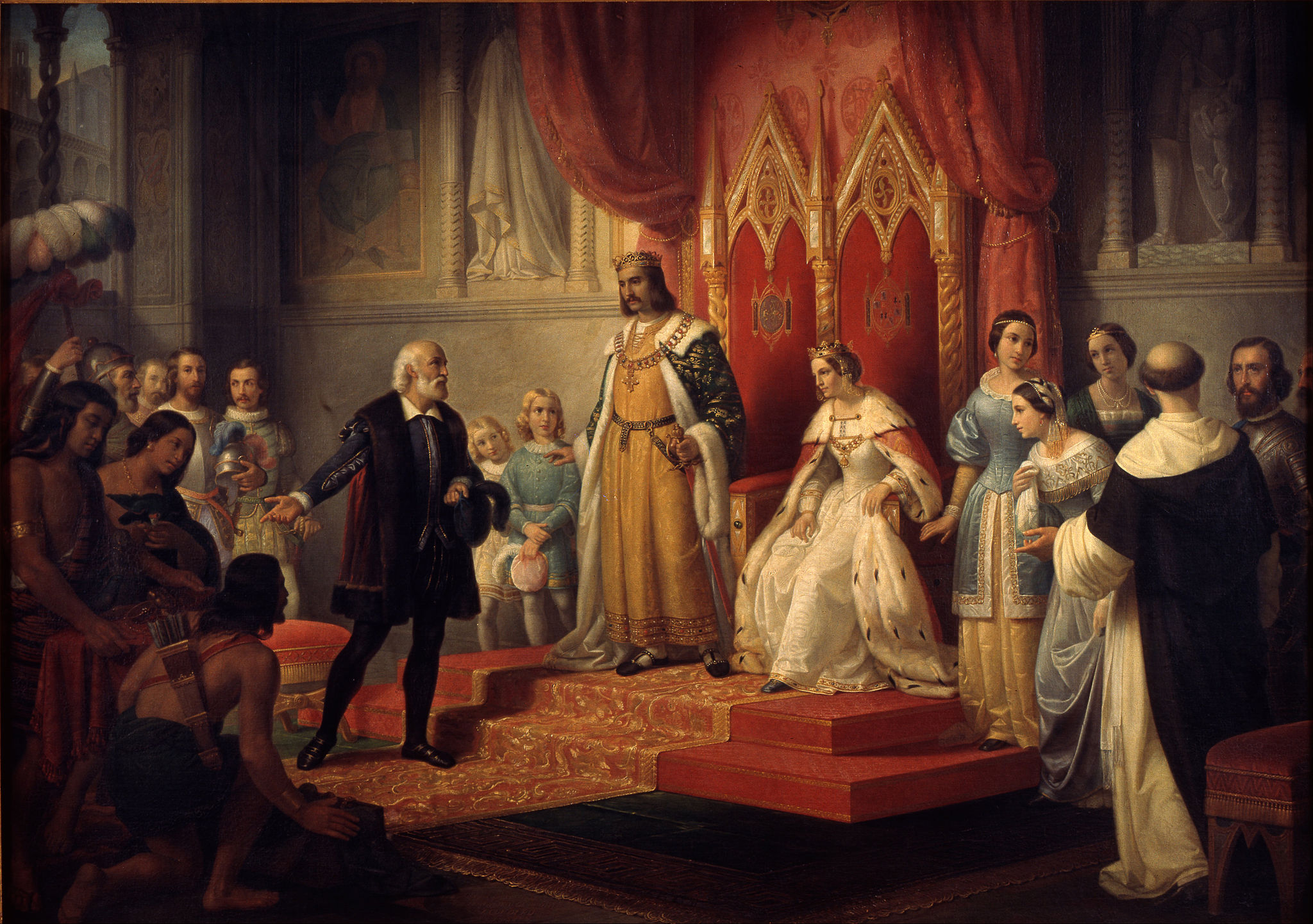

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) was an Italian navigator in the Castilian service who discovered America in 1492 during the race with Portugal for an alternative sea route to India. Around 1480 Columbus, at that time a Genovese sugar merchant, married Filipa de Moniz, the daughter of Bartolomeu Perestrelo, the first Governor of Porto Santo, a sugarcane plantation owner in the archipelago of Madeira.

On his voyages of discovery between 1492 and 1504, Columbus mainly headed for the Greater Antilles, including Hispaniola (today Haiti and the Dominican Republic). On his second voyage in 1493 he introduced sugarcane successfully to Hispaniola.

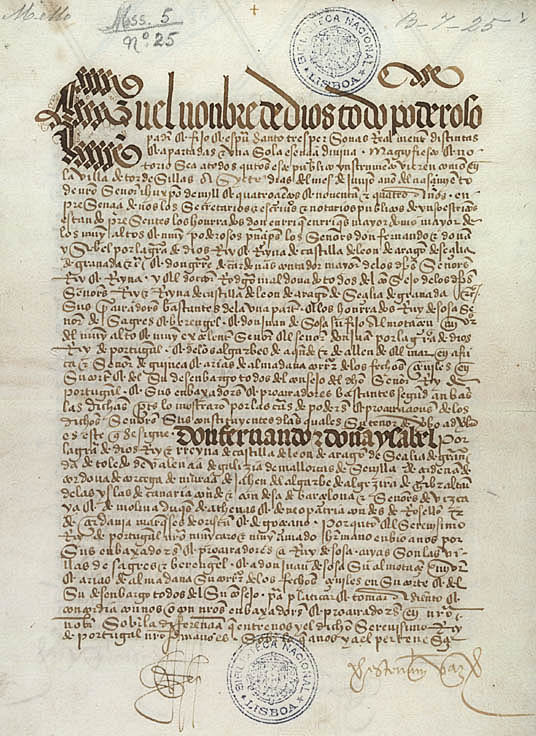

Treaty of Tordesillas

In 1494 the Spanish-born pope Alexander VI forced an agreement between Spain and Portugal settling conflicts over lands discovered two years prior by Christopher Columbus. The Spanish rulers Ferdinand and Isabella asked for the papal support to claim parts of the New World by setting up a line of demarcation from pole to pole at first at 100 leagues (320 miles) – later moved to 370 leagues (1,185 miles) west of the Cape Verde Islands. All territories west of the demarcation line was given to Spain and the Portuguese King John II (after 1495 King Manuel I of Portugal) kept the rights to explore everything east of the line. The treaty was sanctioned by Pope Julius II in 1506. Due to the fact that the new boundary line included parts of the coast of Brazil, the Portuguese claimed these territories discovered by Pedro Álvares Cabral in 1500 in the name of King Manuel I of Portugal.

Further research is needed to determine when exactly the innovators of the Madeira sugar industry started to distill the “skimmings” and byproducts such as molasses to alcohol and shared their knowledge with Colonial Brazil.

Whereas the arrival of the first still in Pernambuco remains unknown, there are indicators that knowledge may have transferred in the late 16th to early 17th century.

Brazilian Engenhos

Sugarcane was introduced to Brazil by the Portuguese in the beginning 16th century. Engenhos is the Portuguese term for a sugar cane mill and all associated facilities (in Spanish ingenios). As the Portuguese became the leading power in the sugar industry in the 16th century with Madeira being the technical innovation center their goal was to further strengthen the Portuguese sugar monopoly by establishing sugar factories along the African coastal islands and in the captaincies of the New World. From the 15 original Brazilian captaincies, only two, Pernambuco and São Vicente, prospered. Whereas Pernambuco, the captaincy of Duarte Coelho, was especially successful installing engenhos as early as 1542, parallel to first importation of African slaves starting that same year.

Martim Afonso de Sousa’s captaincy of São Vicente also produced sugar but its main economic activity was the quest for gold and the traffic of indigenous slaves.

Dutch Brazil (New Holland)

After an unsuccessful attempt to gain power over Salvador in 1624, the Dutch West India Company (WIC) obtained power in 1630 over the Brazilian captaincy of Pernambuco, one of the largest sugar producing areas in the New World. The successful Dutch invasion of the WIC in 1630 did not only remove a large proportion of Brazilian sugar production from Portuguese control thus enabled the Dutch to gain access to the state of the art technology of the sugar industry.

Count Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen, who served for the WIC as Governor of Dutch Brazil from 1637 to 1644, expelled the Jesuits from Dutch Brazil territory and tolerated religious freedom especially so for the Portuguese residents, mainly New Christians (converted Jews that were persecuted in the Old World). It is to be discussed if and to what extend overlapping religious interests, and especially those of Jesuits and Sephardic Jews may have had effects on the knowledge transfer of the sugar industry in the Americas including the distilling of alcohol. The Portuguese won a significant victory at the Second Battle of Guararapes (1649), and the Dutch were forced surrender and capitulate in 1654 which ended the Dutch colonization of Brazil.

Barbados Sugar Industry

When Richard Ligon, an English author and adventurer visited the English colony of Barbados in 1647, Dutch Brazil’s power already began to decline. Ligon described in his travel report that a sugar cane production facility including a still house was newly delivered from Pernambuco and installed in Barbados. He also is the first to mention “Rumbullion” and “Kill-Divil”, two local drinks which are often associated as early rum products.

Reverend Emmanuel Downing’s sons visited Barbados in 1647 as well learning about molasses distilling, bringing this knowledge to Salem, Massachusetts.

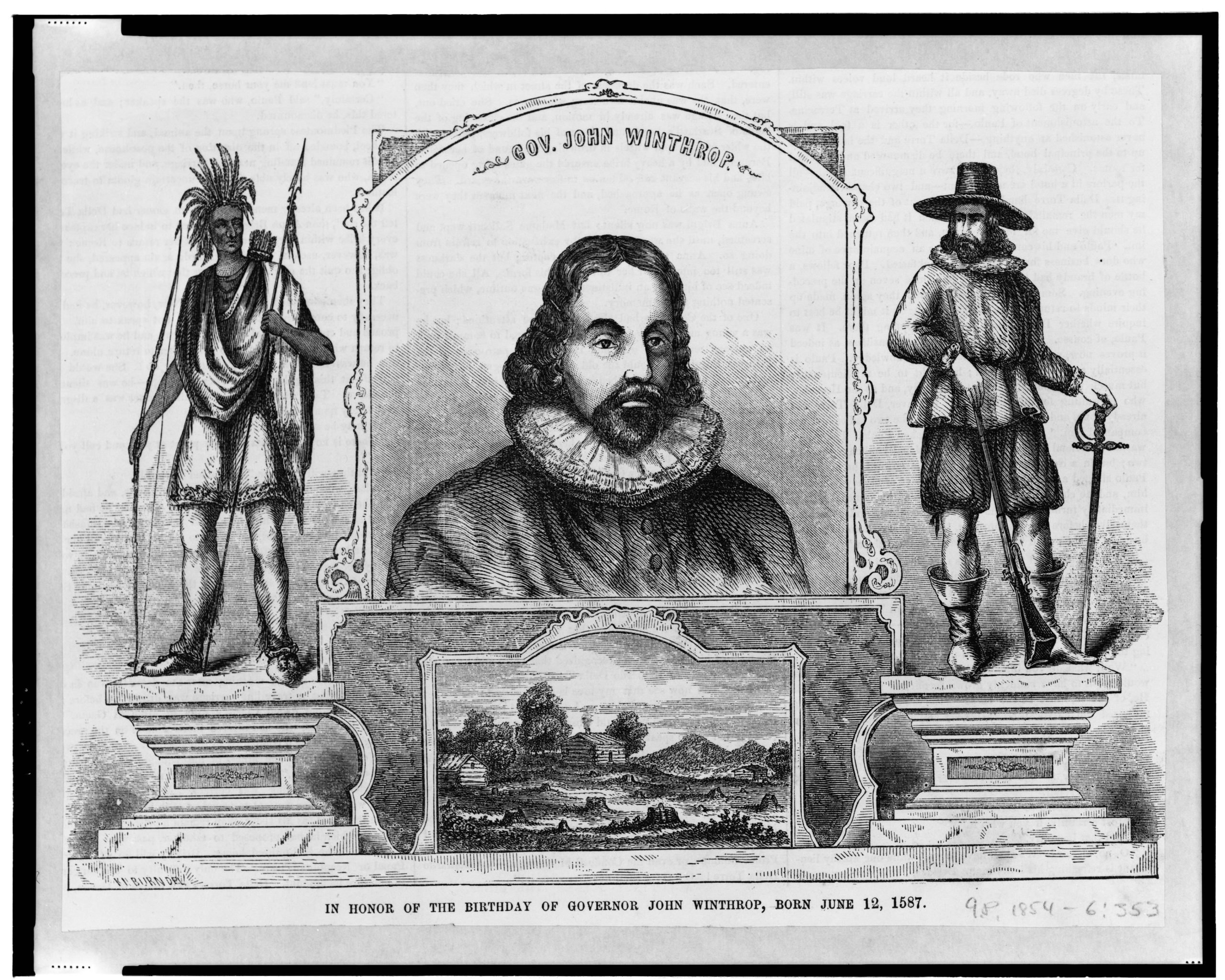

Emmanuel Downing

Reverend Emanuel Downing migrated to New England during the Puritan Great Migration (1620-1640). His family settled near Salem, and with support of his brother-in-law John Winthrop, he quickly established a position in the upper ranks of the town. His wife Lucy (Winthrop) Downing writes in 1648 “When our men found in the West Indies that a strong drink could be made of molasses, they took up the manufacture without delay.” The same year Emmanuel Downing writes to Winthrop “I am now fullie furnished for my stilling buisines”, and that rum from his distillery “is desired more and rather than the best spirits they bring from London”.

Despite Emmanuel Downing did historically not turn out being a successful business, he was though one of the first rum entrepreneurs in the Americas, distilling rum as a primary product and without producing sugar.

Lucy (Winthrop) Downing

In 1636, Gov. John Winthrop raised funds to establish Harvard College. Lucy Downing is sometimes referred to as the “mother of Harvard” due to complaining about the lack of education for her son George in the New World. She may have influenced her brother, Gov. John Winthrop who needed the new generation of Puritan ministers in the colony well educated. Lucy’s son, George Downing attended the first class of Harvard from 1640 to 1642.

Sir George Downing

George Downing was an English statesman, soldier, diplomat, spymaster and preacher. Different than his father he became a successful business man floating with the tides. Downing Street in London is named after him, as well as two streets in New York (one in Greenwich Village and one in Brooklyn) because he played a significant role in the acquisition of New York from the Dutch.

1703 Mount Gay Rum

Barbados markets worldwide its Mount Gay Rum distillery, founded in 1703, as the “birthplace of rum”. There are though historic arguments that challenge this title:

Reverend Emmanuel Downing 1648

started to distill rum at his Salem distillery fifty-five years earlier. His distillery was like Mount Gay Rum not a sugar plant thus a “real” commercial distillery focused only on the production of liquor for consumption.

Knowledge Transfers 1442-1530

Rum distilling knowledge transferred to Barbados from Pernambuco. The idea of creating rum from molasses was born and developed somewhere else.

Rum’s Real Birthplace

Barbados build its first sugar plantation with still house shortly before 1648, importing the knowledge from at this time Dutch Brazil Pernambuco colony. The captaincy of Pernambuco under Duarte Coelho received as early as 1542-55 knowledge transfers from Madeira including the equipment to setup an engenho (sugar factory).

The technological development and idea of distilling rum as a drinkable distillate made of sugar production byproducts like molasses or “skimmings” of sugar cane, needs likely to be accredited to Portuguese Madeira islands first and later to Portuguese Brazil. Further research is needed to examine the early history of rum production in Madeira and Brazilian Pernambuco, as well as along the African islands (feitorias).

Brazilian rum is protected by US law, and marketed exclusively as cachaça.

Breaking of the Sugar Monopoly and Molasses Rum

As the Dutch gained the sugar production knowledge conquering Pernambuco in 1630 they broke the Portuguese sugar monopoly. This caused a rippling effect of knowledge transfers throughout the Caribbean, including Barbados, and the trading posts of the north American colonies. The Dutch West India Company (WIC) was focused on trade maximization over Portuguese colonization style populating and developing the terretories. It is remarkable that the Downings learned almost as early as Barbados sugar planters about the distilling of molasses and switched from distilling rye whisky to molasses rum at Salem distillery as early as 1648.

Annie H. Thwing mentioned rum distilleries prior to 1641 in Boston, Massachusetts. As there is no proof for their existence yet, it is though possible considering a Dutch knowledge transfer since 1630. Due to the newly gained access to the sugar production industry, Dutch traders of the WIC faced for the first time an intensified need to find new markets to sell molasses, a byproduct produced in large amounts in Pernambuco’s sugar factories. This could explain why the Downings and Richard Ligon visited Pernambuco in 1647-48 when the sugar factory was installed. It was a showcase of modern sugar technology of its time, visited by young entrepreneurs and adventurers from around the world.

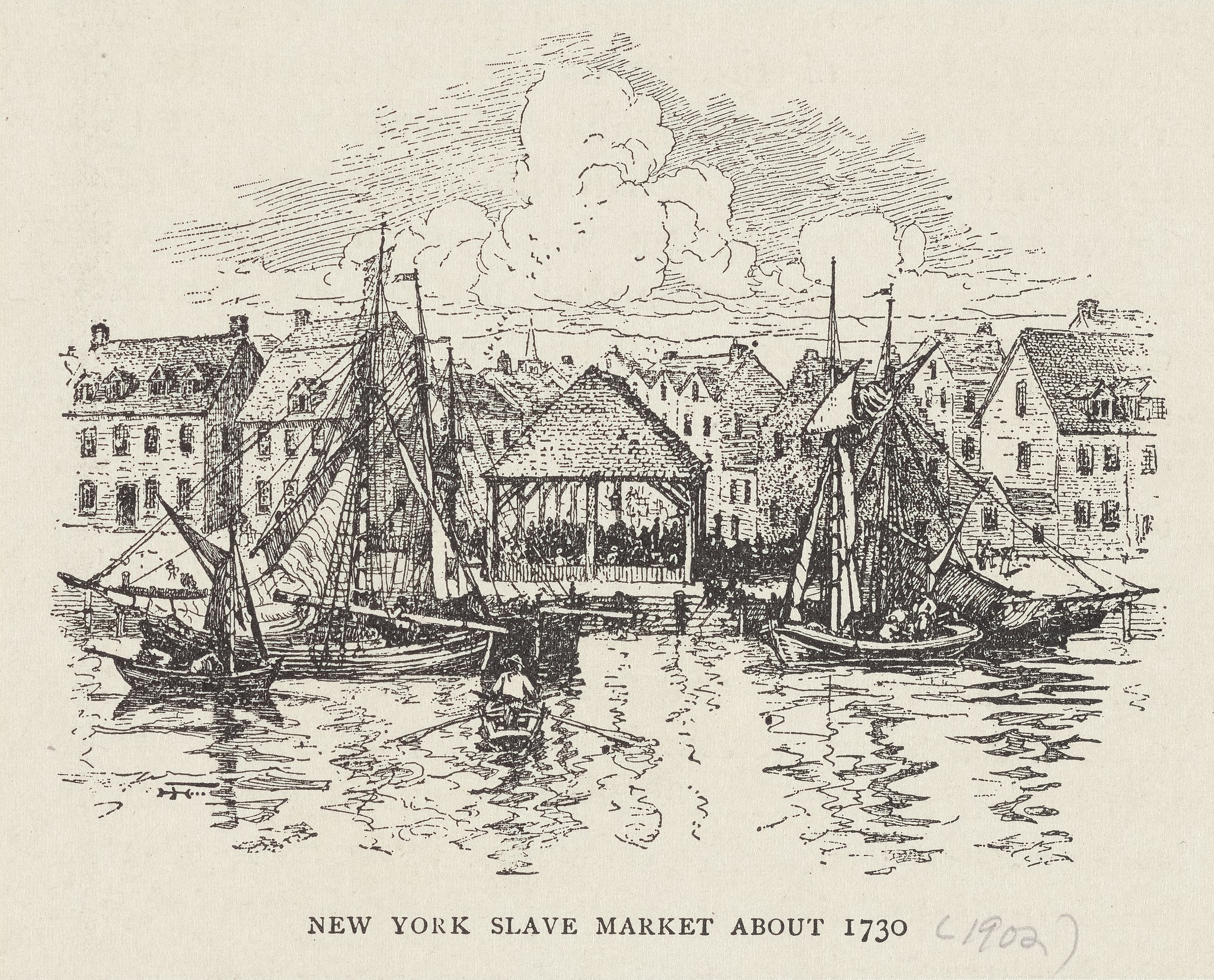

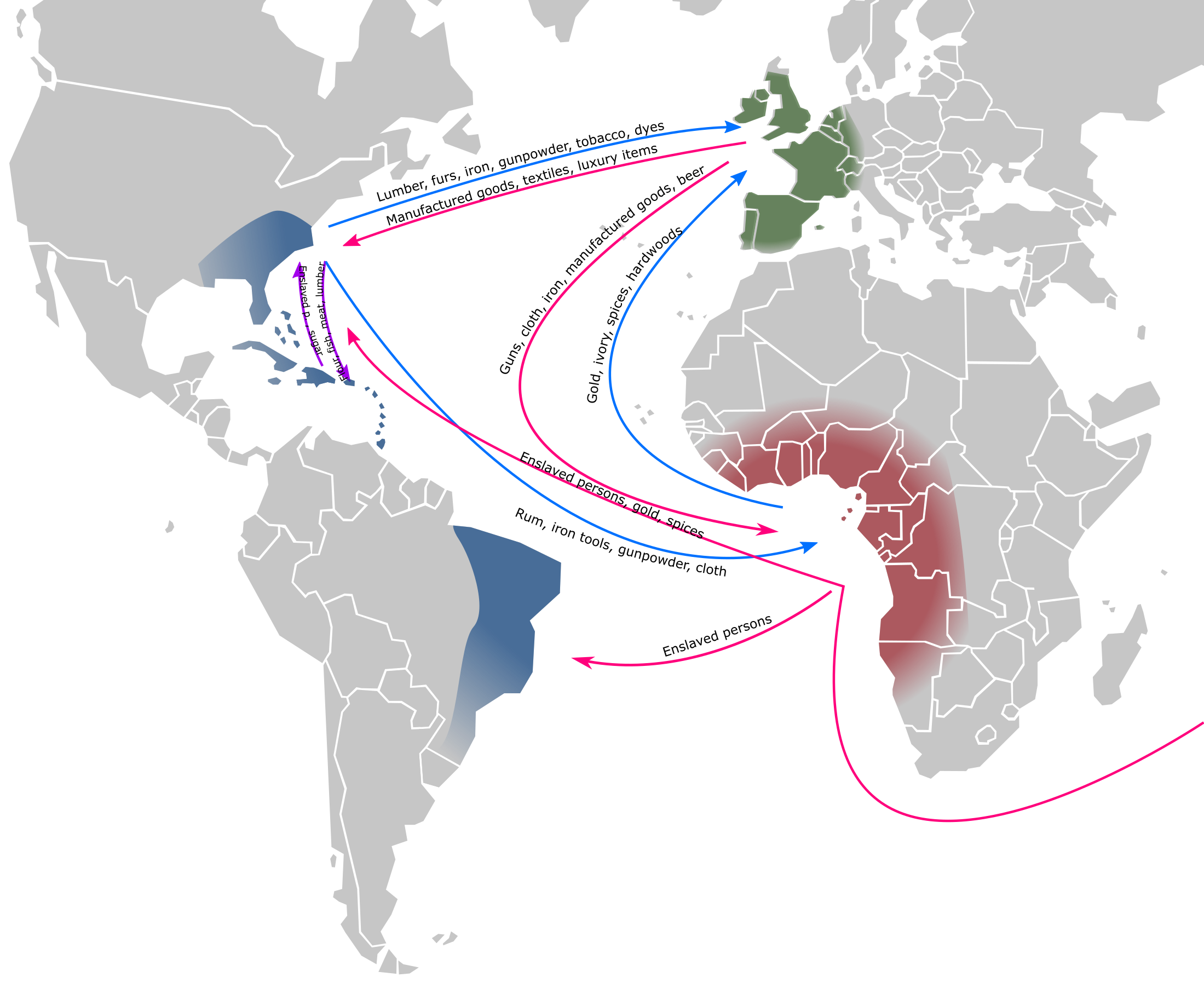

Triangular Trade

Triangular trade (triangle trade) is a term for trade involving three ports or regions. The transatlantic slave trade that emerged during the late 16th to early 19th centuries, was connecting the trade posts of Europe with West Africa and the Caribbean Islands and/or American colonies.

The same regions of this triangle are later also referred to for the colonial molasses trade. When the North American colonies learned to product finish molasses to rum it soon became an important economic factor, as it was a desired commodity for trading. As a matter of fact it should become one of early colonial New England’s largest and most prosperous industries securing their share in the triangular trade.

Amsterdam “Port Jews”

In 1645 the Portuguese began to conquer their former territories in Brazil. As these colonies fell back under Portuguese law the religious freedom the New Christians (Jews) under the Dutch ended. Forced to either live illegally under Portuguese rule, about 200 families decided to migrate back to Amsterdam. The former triangular commercial network of Sephardic Jews that tied together ports in Portugal, northeastern Brazil, and Amsterdam had Brazil now taken out of their trade routes. Amsterdam Sephardim Jews tried to rebuild the trade over the Atlantic, especially as Amsterdam faced an economic boom upon their return. Jewish communities that grew after the Brazilian exodus were Barbados, Martinique, and New Amsterdam. It needs to be discussed if the history of the “Port Jews” may have had a boosting effect for distributing and transferal of the molasses distilling knowledge in the Americas.

Rule, Britannia!

The Caribbean became (after first failed colonization attempts) England’s most important and lucrative colonies. The first successful colonies were established in 1634 in St. Kitts, 1627 in Barbados and one year later in 1628 in Nevis following soon the example of Pernambuco installing sugar cane plantations. In the beginning Dutch traders offered to sell sugar plantation knowhow, trade the slaves and buy the sugar to the new established English colonies.

As the very profitable sugar and slave trade established on the English Caribbean islands the desire of the English grew to maximize profits. This lead to the 1651 Parliament decree allowing that only English ships would be able to ply their trade in English colonies. This decree caused indeed disturbances with the United Dutch Provinces who were providing slaves and traded the sugar off the Caribbean islands, and it finally lead to a series of Anglo-Dutch Wars. In the aftermath, England’s position in the Americas was strengthened at the expense of the Dutch traders, and England was on its way to establish an enduring British supremacy in the triangular sugar and slave trade.

Rule, Britannia! Original lyrics

When Britain first, at Heaven’s command

Arose from out the azure main;

This was the charter of the land,

And guardian angels sang this strain:

“Rule, Britannia! rule the waves:

“Britons never will be slaves.”

The nations, not so blest as thee,

Must, in their turns, to tyrants fall;

While thou shalt flourish great and free,

The dread and envy of them all.

“Rule, Britannia! rule the waves:

“Britons never will be slaves.”

Still more majestic shalt thou rise,

More dreadful, from each foreign stroke;

As the loud blast that tears the skies,

Serves but to root thy native oak.

“Rule, Britannia! rule the waves:

“Britons never will be slaves.”

Thee haughty tyrants ne’er shall tame:

All their attempts to bend thee down,

Will but arouse thy generous flame;

But work their woe, and thy renown.

“Rule, Britannia! rule the waves:

“Britons never will be slaves.”

To thee belongs the rural reign;

Thy cities shall with commerce shine:

All thine shall be the subject main,

And every shore it circles thine.

“Rule, Britannia! rule the waves:

“Britons never will be slaves.”

The Muses, still with freedom found,

Shall to thy happy coast repair;

Blest Isle! With matchless beauty crown’d,

And manly hearts to guard the fair.

“Rule, Britannia! rule the waves:

“Britons never will be slaves.”

Source The Works of James Thomson (1763)

…rule the waves

The patriotic “Rule, Britannia!” song was texted by James Thomson, music by Thomas Arne in 1740. It became popular in 1745 when performed in London. Despite Britain did not “yet rule the waves” in 1745, the song transported the zeitgeist and England’s naval goals. It became an unofficial national anthem that is popular in Great England until today, and it is strongly associated with the British Royal Navy.

Sugar plantation owners in the Caribbean are told to have sold discounted rum to the naval ships providing protection from pirates at their shores.

Naval (Navy) Rum

In 1740 Admiral Edward Vernon introduced rum rations (tots) to the Royal Navy as he sailed to the West Indies. Instead of former beer rations for sailors, rum was diluted with water. The advantage of rum was its better storage life and due to its higher proof also a “condensed” volume ideal for using it as ship rations. Admiral Vernon was named “Old Grog” due to wearing a cloak made of grogram, a coarse fabric made of silk. Him to honor, a drink made of rum diluted with water was named Grog.

As naval rum picked up as a navy drink worldwide, the European market for rum started to develop too, especially in the late second half of the 18th century.

Colonial Molasses Trade

The Caribbean molasses trade was the foundation of colonial commerce that empowered the English colonies to gain from the product finishing process of distilling rum. As the Dutch and French colonies in the Caribbean engaged only little in distilling molasses, the English Caribbean sugar islands distilled rum from the 1650s on to profitably dispose of their molasses. In 1702, Barbados produced two hundred thousand gallons of rum, and the demand for rum as a commodity in the world market was rising. Barbados first rum distillery was founded in 1703 to address this new demand for rum as a commodity beside sugar. By the time of the Molasses Act in 1733 Barbados produced more than 4 million gallons of rum annually and the rum industry was further growing in the Americas in the years to follow.

The Molasses Act 1733

The English sugar plantation owners of the West Indies exported only small amounts of molasses in the 18th century due to distilling most of it on the islands themselves. The Molasses Act of 1733 based though on the claim to protect the English sugar planters from foreign competition in the molasses trade – which kind of contradicted itself. Fact is, that the English sugar planters were facing distilling competition from the North American colonies in the production of rum. And, to drive New England distilleries out of business, the Molasses Act would ensure that taxes were imposed on molasses, sugar, and rum imported from non-British foreign colonies into the North American colonies.

The Molasses Act was broadly violated by New England colonists, cheap foreign molasses was smuggled from Dutch and French Caribbean territories in large amounts. The rum exports of this period can only give a vague idea as rum was consumed in significant volumes in the colonies themselves without ever being exported.

The Sugar Act 1764

After the The French and Indian War had ended in 1763 the British Empire’s desire to collect revenue and funds of the New England colonists grew. Due to the persistent violation of the Molasses Act of 1733 British Parliament focused on ending the smuggling of sugar and molasses from the French and Dutch West Indian Islands in 1764.

The Sugar Act (also named Plantation Act or Revenue Act) of 1764 focused on increasing revenues by enforcing customs of duties on refined sugar and molasses imported to the New England colonies from non-British sugar islands of the Caribbean. Despite the fact that the Sugar Act reduced the tax for molasses compared to the Molasses Act, the enforcement of a tax on molasses caused and immediate effect in the rum production industry of New England. By 1770 New England Colonists had established about 148 distilleries in the thirteen colonies of which most produced rum from molasses in considerable volumes. Taxing on Molasses meant that one of the most important industries of the thirteen colonies was taxed significantly by a Parliament in London to which New England’s colonists had no right to elect a representative speaking for their needs.

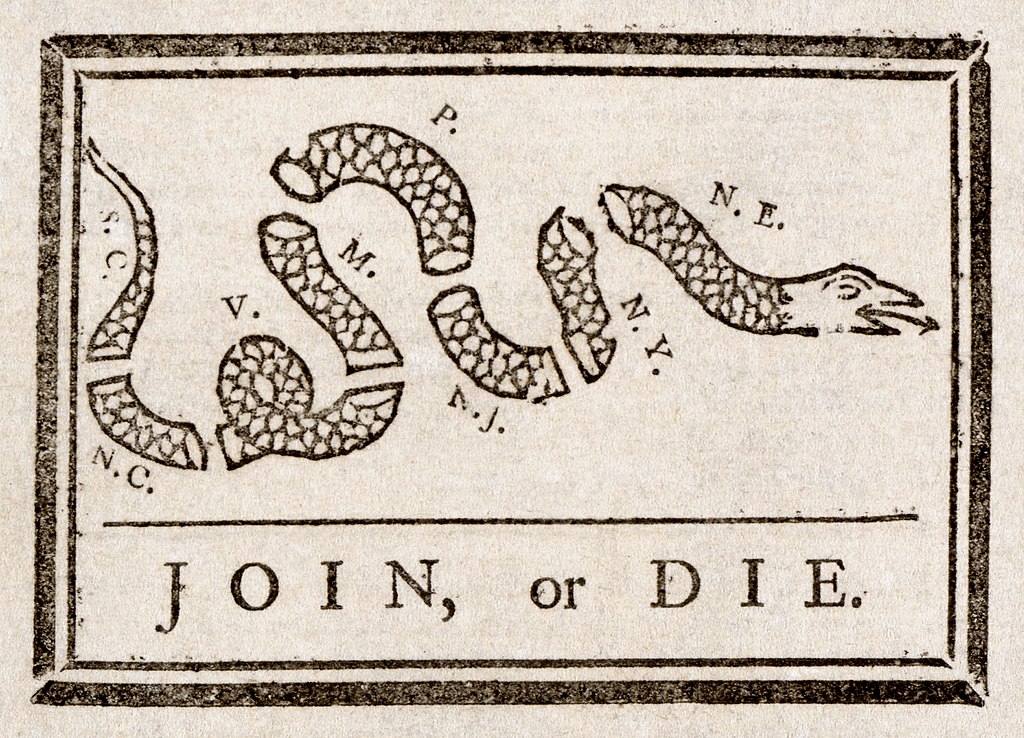

“Taxation without representation is tyranny”

This anti-British slogan used since ca. 1765 rooted in the resentment of New England colonists being taxed by a British Empire that refused them the right to elect representatives. It stands for the beginning American Revolution and America’s Independence.

A M E R I C AN R U M

American Rum, the product that lead America to its independence

American Rum was one of the first industries that made America independent by creating revenues finishing molasses to rum.

The history of rum is indeed fascinating, since its first distilling as a former inferior byproduct it developed over time to a luxury drink that is one of the most used ingredients in cocktails all over the world today.

Rum made from molasses is no longer a byproduct of the sugar industry because technological development has improved the sugar refining processes significantly and reduced the amount and quality of molasses as a left over. Therefore, modern sugar plants distill today only industrial alcohol as a byproduct.

American Rum distilled from molasses will need though a molasses that is cooked in the “old style”, especially made for the spirit industry, so that drinkable rum can be produced. Most molasses rums are appearing to be “rounder, sweeter, cleaner” in taste comparison to rum made from fresh sugar cane juice with normally more dominant “grassy, vegetal, earthy” elements.

The history of American Rum is the history of the first international trade network with the Americas that developed as early as the 16th century across the Atlantic. This trade network showed economic stability despite of wars or shifts of power from one nation to another. It outlived religious lobbying, and technological transfers across the Americas. Sugar and molasses trade were up to the American revolution a constant growing industry that allowed the colonists of the Americas to gain revenues they needed to become independent of the colonial powers in Europe.

Rum production played a significant role in the years after the revolution, and if not for the noble experiment of the Prohibition from 1919/1920 to 1933 it might have remained a significant product made in USA, likely as important as bourbon is today.

It is time to honor American distillers and American history. AMBRU Campaign is not claiming the birthright of inventing rum as a product but of its first production: American Rum clearly outdates Barbados oldest distillery, its importance as an early commodity for trading enabling America to become independent, and its uniqueness in taste made with North American white oak barrels.