Commercial Distilling in North America

Commercial distilleries are defined by having been granted distilling rights with the primarily goal to distilling alcohol products and involving in local, and/or international trade.

It is historically important to differ commercial productions from private distilling activities as quantities of commercial distilleries have to outgrow local needs to engage in international trade. Commercial distilleries are therefore likely to significantly impact socially and economically by creating revenue and jobs whereas private distilling activities may play no significant role.

Distilling is more than a craft that one simply learns. It is an art creating spirits with local products that capture the uniqueness of their origin in the final distillate. It needs creativity and lots of passion for distilling, as it is hard work until a spirit is perfectly balanced in ones glass and telling its story.

Aqua Ardens & Aqua Vitae

The earliest mention of drinkable alcohol was in 1150 by the “Master of Salerno”, alias “Salernus” in the “Mappae Clavicula” where he describes a first recipe for the isolation of alcohol and refers to it as “aqua ardens” describing the burning quality of the alcohol distillate.

Aqua vitae is a term that derived from the alchemistic believe to find the “water of life” or the all healing remedy. This term aqua vitae was used later mainly for distillates with a higher alcohol concentration which was achieved with improvement of distilling equipment. Thereby it is important to note that all distillates at this time were made from wine. The distilling of grain was not yet developed and the term aqua vitae predominantly refers to early types of brandy rather than whiskeys.

1620-22 George Thorpe

George Thorpe (1576-1622) was a Virginia colonist, also known as being one of the “Berkeley Hundred”. In 1620 he wrote:

“Wee haue found a waie to make soe good drinke of Indian corne as I ptest I haue diuerse times refused to drinke good stronge Englishe beare and chosen to drinke that.”

This quote is often referred to as a first proof of bourbon distilling activity in North America, thus his “corne drinke” Thorpe refers to was rather likely a form of beer made from corn as he compared it to English beer and does not refer to it as a strong water, aqua vitae or aqua ardens, nor compared it to any of those – which would have been correct terminologies in his time for distillates.

When in 1634 the Virginia Company returned to search for the remains of the Berkeley Hundred and George Thorpe who died in a raid of natives in 1622, they registered among George Thorpe’s possessions a “copper still, old”.

So, George Thorpe may have been very well the first settler that is today known to have distilled in North America thus not yet the first commercial distiller yet.

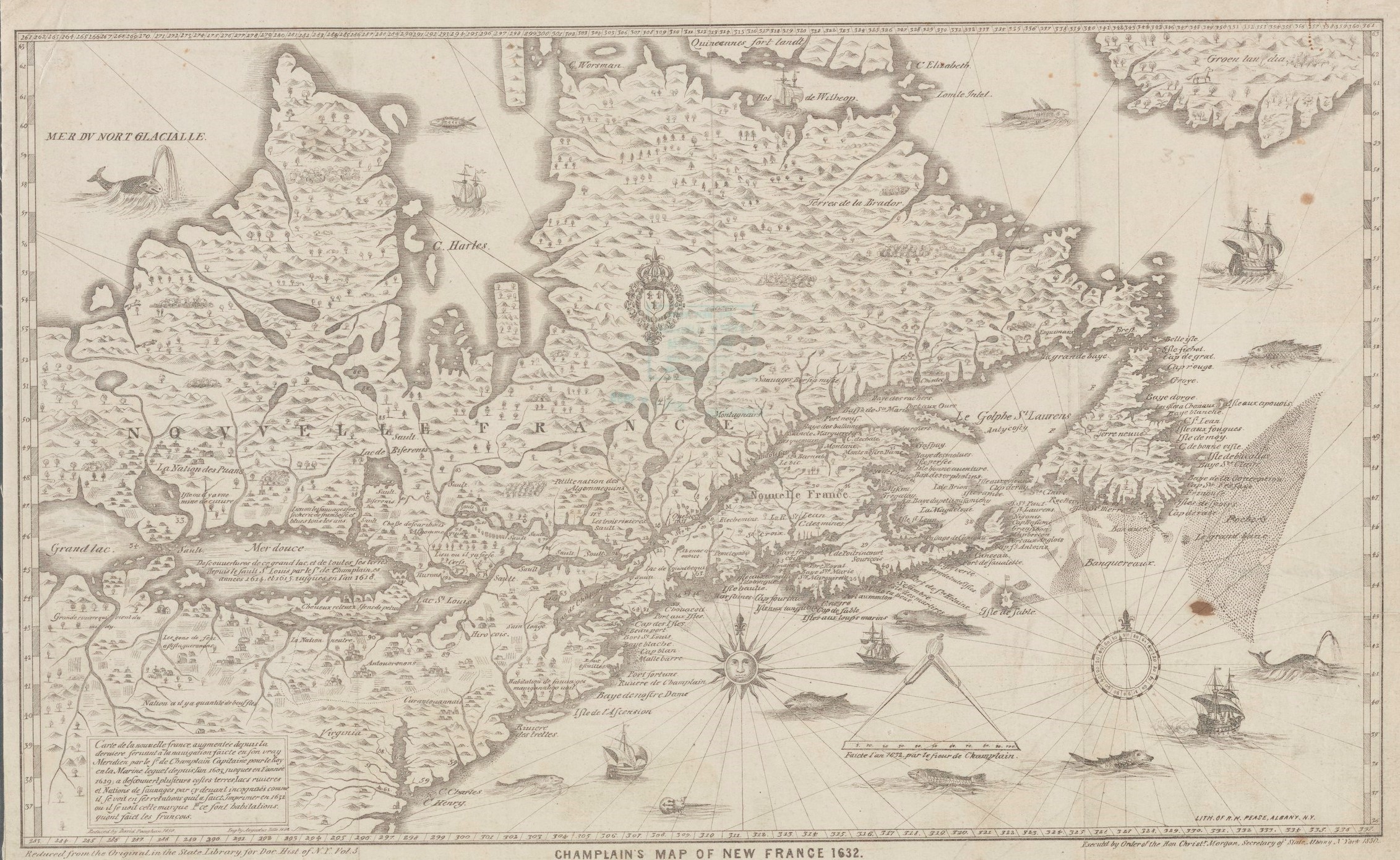

1632-34 Jacob Albertsz Planck

When in 1632 the New Nederland West India Company financed 25 men at Fort Orange, one of the first intends of Kiliaen van Rensselaer, one of the founders of the Company, was to support the colony to making profits by building of a brewery, in case of access grain, and to order a brandy distiller with the next ship.

When Jacob Planck, a distiller of brandy from Edam, arrived on the Eendracht ship in 1634 at Fort Orange, New Nederland, he brought as asked a large brandy kettle with him. And, Kilian van Rensselaer granted Jacob Planck the first commercial distilling rights in North American territories and contracted it as follows:

“…Planck, at his own expense and risk and full charge, may distill brandy, anisette or other spirits, or brew beer to be sold to the Company or to the savages, or do otherwise therewith as he shall think fit.”

The Dutch West India Company’s goal of colonization was focused on creating profits by trading products and creating profits for the Company rather than following political goals of building a colony.

Historical Meaning of Brandy

Brandy and liqueur were considered the more desired drinks in Planck’s time as brandy was a valuable drink being made of distilled fruit wines. The distilling of grain was just invented sometime in the 16th century, whereas distilling of fruit brandy was an art known since the 11th century in Europe.

The term brandy is a short form of the Old English brandewine or brandywine. “Brande” translates from both German and Dutch to burning which in both countries is a term for distilling. As though it may be unclear if the Dutch word brandewijn, which derived from gebrande wijn (“burned wine”), or the German term of Branntwein (“burned wine”) or the German term Weinbrand (“wine burned”) were first and name inspiration for the Old English brandewine – both the German and Dutch terms mean the same and describe the same process namely of the distilling of wine.

As the Dutch were building a new and yet unseen trading empire in the early 16th century across the Atlantic, Africa and towards Asia, it is likely that the Dutch term was dominating international trade language, and that the Dutch term was rather name giving for the English term brandy despite the possibility that the German term could be older.

Korn (Grain) Distilling

Korn (German term for grain) is one of the oldest known distillates based on grains that was estimated to be produced in Germany since the 15th century. One of the earliest proof though of Kornbrand (Grain brandy) production is a distilling ban for grains in 1545 in the city of Nordhausen, Germany which at this time had developed to a famous distilling center in Germany. Further is to be researched who may have distilled grain first, whereas the often quoted Red Book of Ossory in Ireland, includes a copy of the recipe of making aqua vitae, the distilling wine. Similar aqua vitae recipes can be found in other monasteries in Europe, they are though yet lacking a proof of knowledge of the grain mashing process used for distilling.

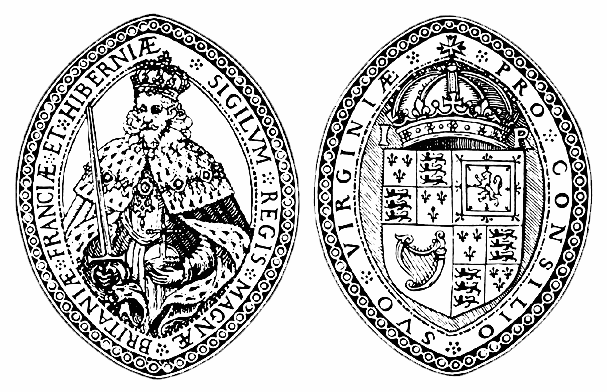

1640-42 Willem Kieft

Willem Kieft became director of New Nederland in 1638. Prior to his arrival, the colony had been run by the Dutch West India Company (Geoctrooieerde Westindische Compagnie/ GWC) which mainly had monopolized trade for their own profit. After Governor Kieft’s arrival he notes that one-fourth of the houses of New Amsterdam are used as brandy-shops which clearly shows that society had started to drink brandy “for pleasure” instead of beer and wine.

By 1640 Kieft established his own brandy distillery at his house in “Manhathans”, New Nederland, which was eye witnessed later at the Court of Holland in 1649 by Cornelis Toun who stated he worked there as a distiller.

Kieft’s distillery is often falsely quoted to be the first bourbon distillery in North America. Kieft was distilling predominantly brandy, as “Its ordered by this Court, that there shall not be any corne nor malt stiled into liquors, in any Plantation in this Colony.”

Banning the distilling of grains was common throughout Europe since the 16th century predominantly to secure food supplies, this distilling ban in the Dutch colony does not surprise at this point.

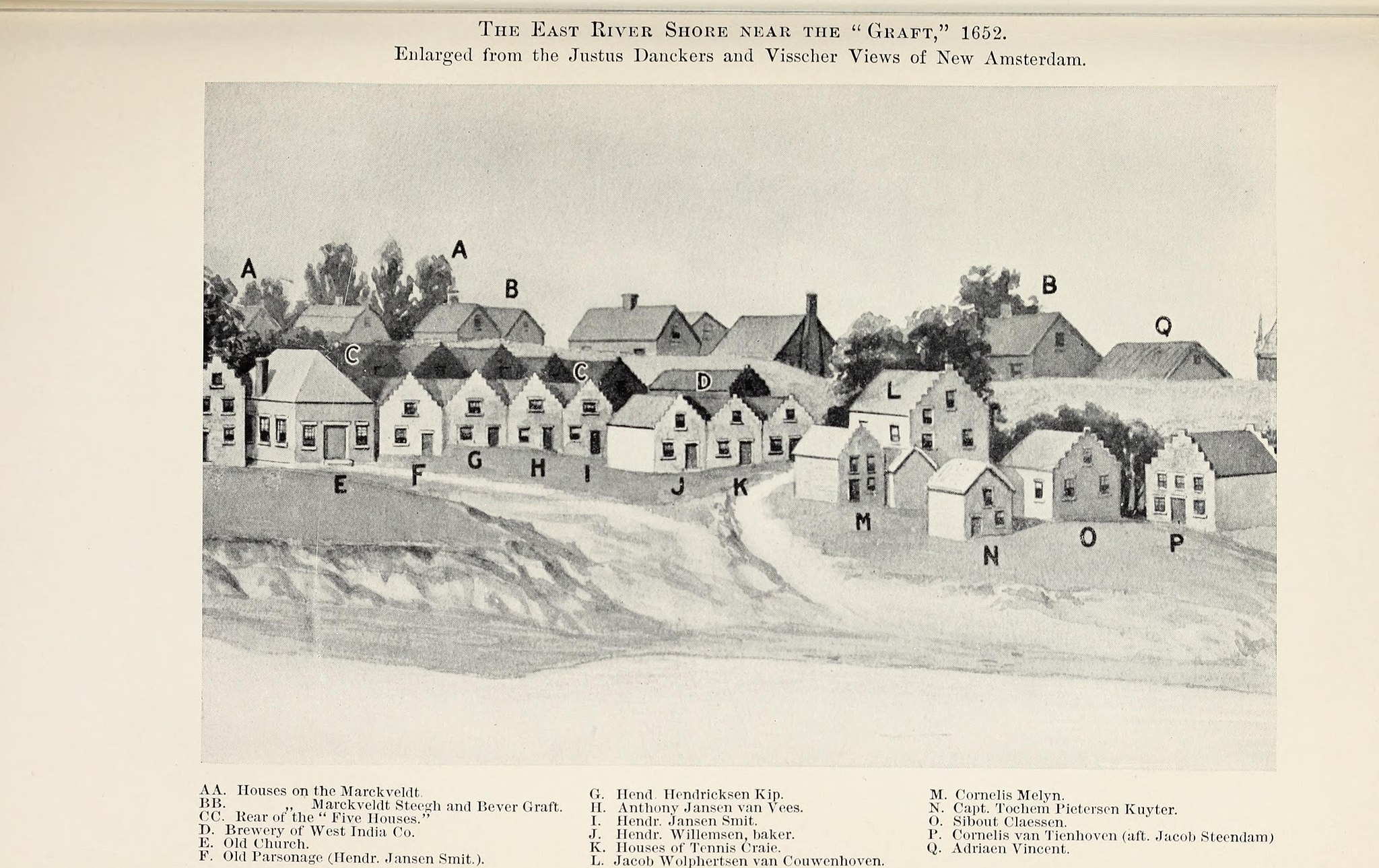

1641 Cornelis Melyn

Cornelis Melyn established a brandy distillery in 1641 on Staten Island. After a dispute with the Dutch West India Company he was granted the remaining part of the island: “De Vries disputed Melyn’s claim but having established himself in Vriesendael consented to Melyn’s occupying 12 to 14 morgens (24 to 28 acres) of land ‘without abridging my rights as he intended to distill brandy and make goats leather.’” Further research is needed to evaluate if Cornelis Melyn may have been engaged in commercial trade. This remains unclear at this point.

1648 Salem Distillery

Reverend Emmanuel Downing started distilling rye whiskey in 1648, thus soon thereafter he switched to distilling molasses rum. Read more about the beginnings of rum distilling in the Americas here.

1641 Boston distilleries?

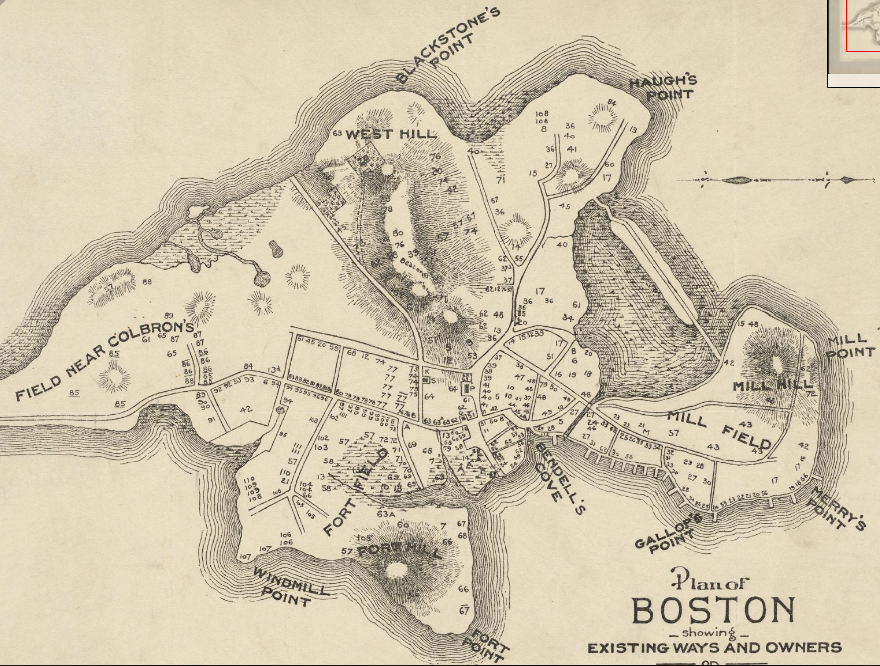

Annie Haven Thwing was an American historian that compiled an enormous card index of subjects related to the history of Boston, Massachusetts. In her 1920 book “The Crooked and Narrow Streets of the Town of Boston 1630-1822” she stated that before 1641 “the distilling of rum was largely carried on, and distilleries were scattered over various parts of the town, but the larger number were in the neighborhood of Essex and Chardon Streets. The professions were represented by the ministers and the physicians or barber-surgeons.” Further research is needed to verify A.H. Thwing’s findings about rum distilling before 1641 in Boston. It is possible that there were distillers in Boston prior 1641, thus it is to be asked if these were commercial distilleries, and if molasses was distilled that needed to be imported from the Caribbean islands rather than brandy products that could have been supplied by surrounding fruit farms.

A M E R I C A N B R A N D Y

American Brandy commercially distilled in North America since 1632

The first, important distillate of the early settlers in North America was brandy.

As the Dutch West India Company started its endeavor and raised money to build first trading posts at the North American continent its intentions were clearly on making profits. Profitable commodities were among fur, timber, and crops, alcoholic beverages and especially so brandy.

Brandy was a desired drink of the upper class, it was introduced as a remedy, and became a popular alternative to beer and wine as it was more durable than the latter. This made distillates attractive for international trade as wine and beer needed to be fortified to be best before arriving at the port of call across the Atlantic or any other far distance. (compare i.e. Indian Pale Ale (IPA) beer)

As society of the late 16th and early 17th century began to change its usage of high proof distillates from former mainly medicinal usage to a culturally accepted “drinking for pleasure”, the gains and profits for this commodity raised with this new need. It is therefore not a surprise that the Dutch West India Company send a large still pot just two years after first settlement to the new established colony in North America.

It is likely that at first the focus was on brandy production due to availability of native fruits (i.e. crab apples), and the larger profit margins, which later should shift toward the even more profitable rum production from molasses when the Dutch connected their new gained territories in the Caribbean and Pernambuco (Portuguese Brazil) to trading posts in North America and Amsterdam in Europe.

Read more about the history of American rum, the fascinating story about a global trade network, pirates, rum, and revolution.