More about geographical indicators and their economic impacts

The origins of geographical indicators are to be found in Europe. With upcoming development of the European colonies knowledge was transferred to places far away from original production, complex supply chains began to develop, and over time trade grew internationally and overall was the tendency to move production towards more profitable regions. Over time trade contracts evolved and were modified, and States of origins learned that it may be profitable to claim the historical originality of a product group.

With quality differences, and marketing goals to protect local production areas by branding regions and/or products the idea of geographical indicators and trademarks was set forth. As diverse as Europe’s countries are as complex is the legal history of the development of international trade contracts, standards and geographical indicators.

What is the difference between a geographical indicator and a trademark?

A geographical indicator (GI) links a product to a specific geographic region, it is designed for different products produced in this specific region whereas trademarks are goods of a certain enterprise normally without any geographical restrictions; meaning the production of a trademarked product can likely be moved to a different location despite its name whereas a GI (geographical indicator) demands the production to remain where the GI determines.

In case of geographical indicators we are more or less thinking of a “collective dimension” rather than a singular product branding.

Is the usage of geographical indicators a pure “linguistic monopolization”?

Critics may argue that the impact of geographical indicators may be less different to creating trademarks, thus it is important to remark that protecting origin-labeled niche markets offers an opportunity to protect and enhance the potential of a certain geographical region. It can be used on a larger scale to support local job markets, and local sales defining a geographically original product for a region. It is a political and economical concept balancing the power of global players trademarking products worldwide without the need to secure production locally.

Geographical indicators are recognized as intellectual property and are playing an increasingly important role in trade negotiations worldwide for the EU and other countries.

What about Geographical indicators for spirits in the EU?

The aims of the EU quality schemes promote unique characteristics of specific products if they are normally linked to a certain know-how, quality and a geographical area of origin. This enables consumers to trust and distinguish certain quality products and it is as well a marketing tool for a group of sellers from a certain area. Whereas Geographical indicators can be used for all kinds of locally produced products, the spirits categories in the EU alone has in July 2021 about 274 registered geographical spirits including Scotch whisky, Brandy de Jerez, and Cognac.

Detailed information and a complete list of all geographical indications registered in the European Union can be downloaded in the eAmbrosia database of the European Commission for geographical indicators.

Why is bourbon not listed as geographical indicator under EU non-EU country spirit drink?

Bourbon is protected under international trade agreement (see IP/94/250) between the European Union and the United States Drink Agreement of 1994.

Under this agreement the US agreed to restrict the use of product designations of Scotch Whisky, Irish Whiskey, Cognac, Armagnac, Calvados and Brandy de Jerez to distilled drinks products of EU member states where they originate. Whereas the EU agreed to restrict the use of the products designations for Tennessee Whisk(e)y, Bourbon Whisk(e)y and Bourbon to distilled US drinks products.

EUROPE

Current geographical indications used in the European Union

PDO – Protected Designation of Origin

Products registered as PDO are for food and wine, and must a very strong link to the place where they are produced. This normally includes that every part of the production process must take place in a specific region, i.e. a wine under PDO the grapes have to come exclusively from the geographical area named.

The French AOC (Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée) standard refers to products meeting the criteria of the PDO and protects the denomination on the French territory.

PGI – Protected Geographical Indication.

Products registered as PGI are a category for food and wine and must have at least one production step taking place in the region of indication, i.e. for wines this means that 85% of the grapes must be grown and processed in the area where indicated.

GI – Geographical indication of spirit drinks and aromatised wines (GI).

GI s are predominantly used for spirit drinks and wines that are originating in a region, country, or locality with a focus on quality, reputation and certain geographical attributes. The production, preparation and distilling needs to take place in the region, whereas the raw products may come from another region. An example is Irish Whiskey which needs to be distilled in Ireland thus its raw materials may be imported to the island.

What does the TTB stand for?

The TTB – Alcohol and Tobacco, Tax and Trade Bureau of the U.S. Department of Treasury is overviewing the licensing of distilleries (and other alcohol producing entities) in the US, it is registering trade names and supervises the labeling of spirits and all related regulations in the United States of America. Details can be found here.

Furthermore, the TTB publishes definitions and standards for alcoholic classes and types of beverages traded in the US including all protected geographical indications that the United States of America has agreed to in international bilateral trade contracts. Further information.

Should a country wish to protect their GI in the US, it needs the US government regulations to define a new Standard of Identity for it. The TTB other than the GI process in the European Union is not an intellectual property agency.

Read more about Congress & bourbon 1964.

Geographically protected brandies in the US

Brandy used to be the most exclusive drink, long before whiskeys became popular. Therefore, it is not surprising to find many known examples of geographical protection, i.e.

PISCO (Peruvian grape Brandy, 1991)

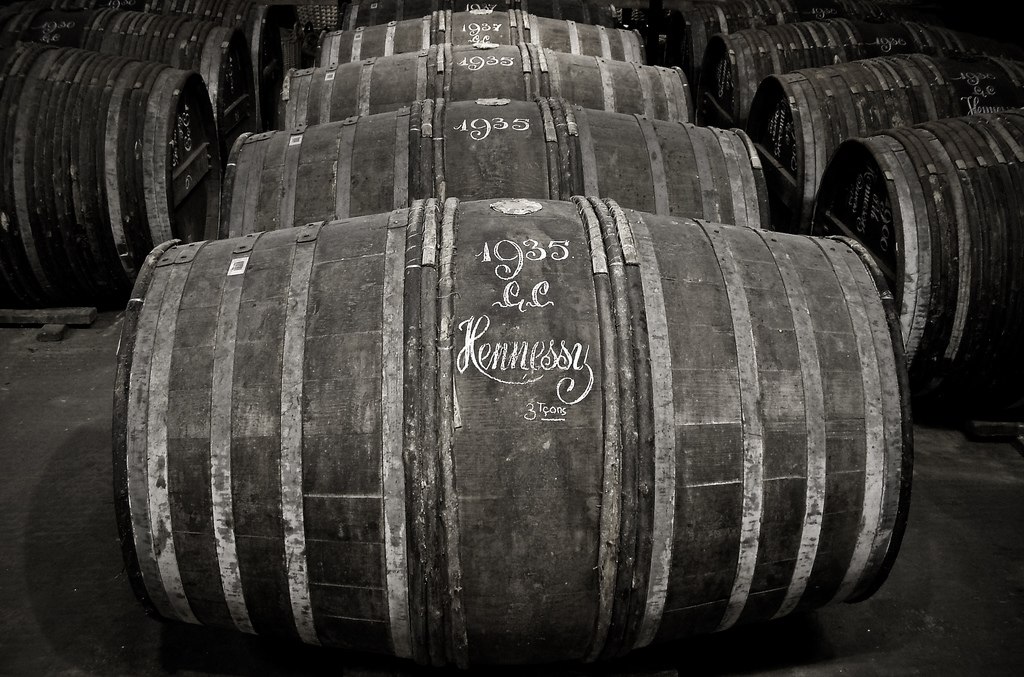

COGNAC (French grape brandy, 1989)

Armagnac (French grape brandy, 1936)

Calvados (French apple brandy, 1942)

Brandy de Jerez (Spanish grape brandy)

Protected rum from different areas in the world

Licensing under geographical indication is a legal process, and the products need to prove its product originality and historical claim to be considered to be protected. Below some products known in the US that have successfully registered GIs or are in preparation. It is important to note that spirit GIs are not automatically recognized by the United States.

Cachaça (Brazilian Rum, 2013)

Rhum agricole (French Caribbean, 1996)

Demerara Rum (Guyana, 2021)

Jamaica Rum, and Jamaica Jerk Rum (Jamaica)

Barbados Rum (Currently in preparation)

Why are geographical indicators a hot topic?

By successfully registering a geographical indicator with the European Union, products receive a much broader protection in EU countries, similar to those of Cognac and Scotch Whisky.

This also means that for smaller regions becoming geographical indicator the production must remain in these regions. As a result jobs could not be outsourced to lower income areas, and production would remain in the country for these signature products.

Furthermore, quality standards for these products are internationally recognized and the overall perception of quality from consumers rises with the trust in a fair local production.

On the long run, geographical indicators help to brand products of origin of a certain region, adding to the overall value proposition of the product and area. After the successful registration of Cachaça in 2013, many Caribbean islands are now in the process to geographically protect their products of origin globally.